New image reveals secrets of planet birth

Tuesday 1 August 2023

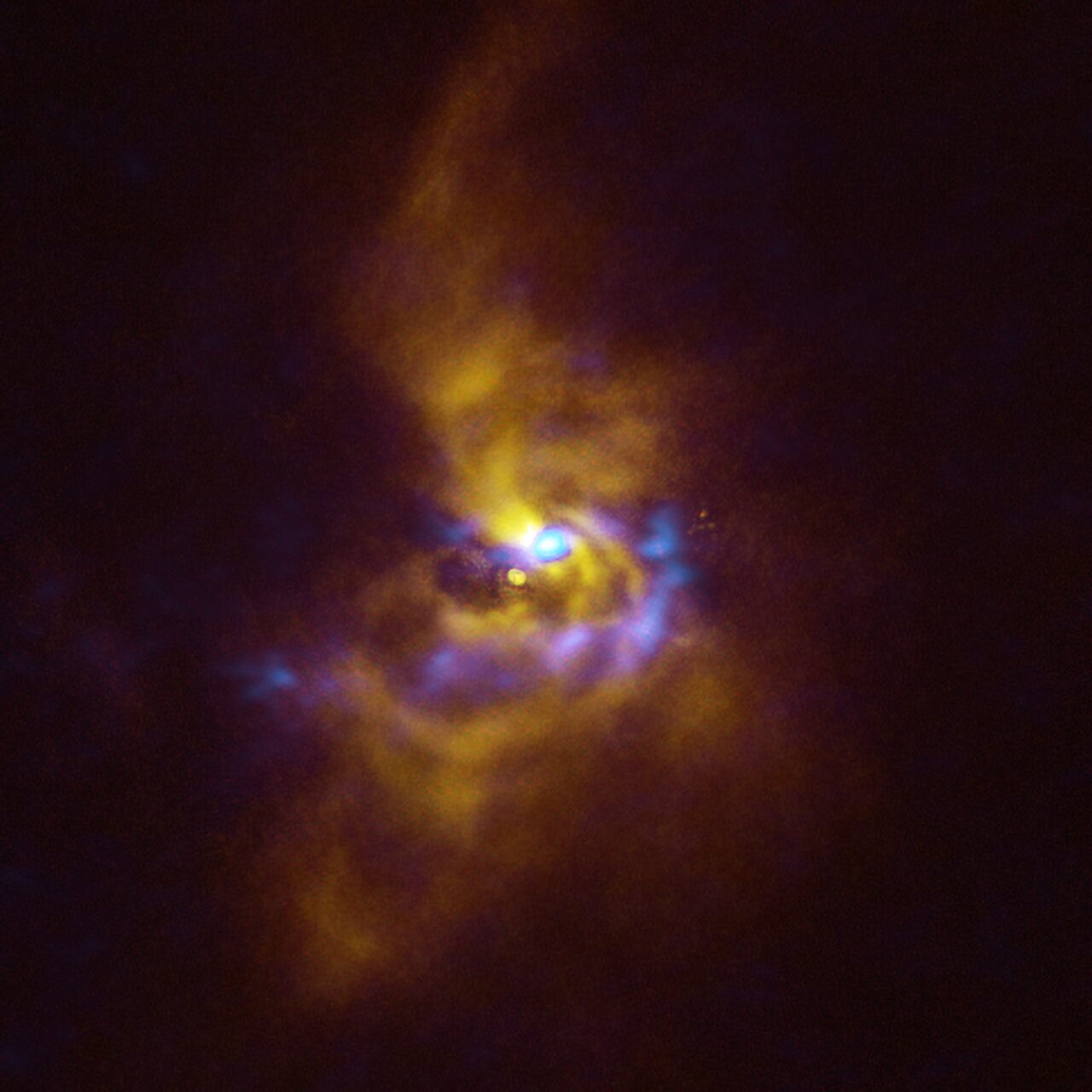

Combined SPHERE and ALMA image of material orbiting V960 Mon - image credit: ESO

25th July 2023. A spectacular new image released

today by the European Southern Observatory gives us clues about how

planets as massive as Jupiter could form. Using ESO’s Very Large

Telescope (VLT) and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array

(ALMA), researchers have detected large dusty clumps, close to a young

star, that could collapse to create giant planets. “This

discovery is truly captivating as it marks the very first detection of

clumps around a young star that have the potential to give rise to giant

planets,” says Alice Zurlo, a researcher at the Universidad Diego Portales, Chile, involved in the observations. The work is based on a mesmerising picture obtained with the Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch (SPHERE) instrument on ESO’s VLT

that features fascinating detail of the material around the star V960

Mon. This young star is located over 5000 light-years away in the

constellation Monoceros and attracted astronomers’ attention when it

suddenly increased its brightness more than twenty times in 2014. SPHERE

observations taken shortly after the onset of this brightness

‘outburst’ revealed that the material orbiting V960 Mon is assembling

together in a series of intricate spiral arms extending over distances

bigger than the entire Solar System. This finding then motivated astronomers to analyse archive observations of the same system made with ALMA,

in which ESO is a partner. The VLT observations probe the surface of

the dusty material around the star, while ALMA can peer deeper into its

structure. “With ALMA, it became apparent that the spiral arms are

undergoing fragmentation, resulting in the formation of clumps with

masses akin to those of planets,” says Zurlo. Astronomers

believe that giant planets form either by ‘core accretion’, when dust

grains come together, or by ‘gravitational instability’, when large

fragments of the material around a star contract and collapse. While

researchers have previously found evidence for the first of these

scenarios, support for the latter has been scant. “No one had ever seen a real observation of gravitational instability happening at planetary scales — until now,” says Philipp Weber, a researcher at the University of Santiago, Chile, who led the study published today in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. “Our

group has been searching for signs of how planets form for over ten

years, and we couldn't be more thrilled about this incredible discovery,” says team-member Sebastián Pérez from the University of Santiago, Chile. ESO

instruments will help astronomers unveil more details of this

captivating planetary system in the making, and ESO’s Extremely Large

Telescope (ELT)

will play a key role. Currently under construction in Chile’s Atacama

Desert, the ELT will be able to observe the system in greater detail

than ever before, collecting crucial information about it. “The ELT

will enable the exploration of the chemical complexity surrounding these

clumps, helping us find out more about the composition of the material

from which potential planets are forming,” concludes Weber. More informationThe

team behind this work comprises young researchers from diverse Chilean

universities and institutes, under the Millennium Nucleus on Young

Exoplanets and their Moons (YEMS) research centre, funded by the Chilean

National Agency for Research and Development (ANID) and its Millennium

Science Initiative Program. The two facilities used, ALMA and VLT, are

located in Chile’s Atacama Desert. This research is presented in a paper to appear in The Astrophysical Journal Letters (doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/ace186). Composition of the team: https://www.eso.org/public/news/eso2312/?lang

Links

|