|

|

Posted By Administration,

Wednesday 20 October 2021

Updated: Tuesday 19 October 2021

|

In

2013, the European Physical Society launched the Emmy Noether

Distinction to recognise noteworthy women physicists having a strong

connection to Europe through their nationality or work.

Emmy

Noether, with her fundamental and revolutionary work in the areas of

abstract algebra and on the conservation laws in theoretical physics, is

an exceptional historical figure for all generations - past, present

and future - of physicists.

The laureates of the Emmy Noether

Distinction are chosen for their capacity to inspire the next generation

of scientists, and especially encourage women to pursue a career in

physics. Attribution criteria therefore focus on the candidate’s

• research achievements

• endeavours in favour of gender equality and the empowerment of women in physics

• coordination of projects and management activity

• committee memberships

• teaching activities.

Nominators are encouraged to address these five points in their proposal.

The EPS Emmy Noether Distinction for Women in Physics is awarded twice a year, in winter and in summer.

The

selection committee, appointed by the EPS Equal Opportunities

Committee, will consider nominations of women physicists working in

Europe for the 2021 Winter Edition of the Emmy Noether Distinction from

the end of October 2021. As is customary for the Winter Edition of the

Distinction, particular attention will be paid to senior candidates.

For the present edition, the deadline for nominations is extended to November, 1st 2021.

To make a nomination, please, email the following information to the EPS Secretariat:

- A

cover letter, detailing (in no more than 3 paragraphs) the motivation

for awarding the EPS Emmy Noether Distinction to the nominee;

- The nominee’s name, institution and email;

- The nominee’s CV;

- The nominator’s name, institution, and email.

- Optional: No more than 3 support letters.

Download the distinction charter and read more about the EPS Emmy Noether Distinction on the EPS website.

Tags:

call

distinction

Emmy Noether

EPS Emmy Noether Distinction

EPS EOC

EPS Equal Opportunities Committee

women in physics

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Administration,

Friday 24 September 2021

Updated: Friday 24 September 2021

|

Author: Kees van der Beek

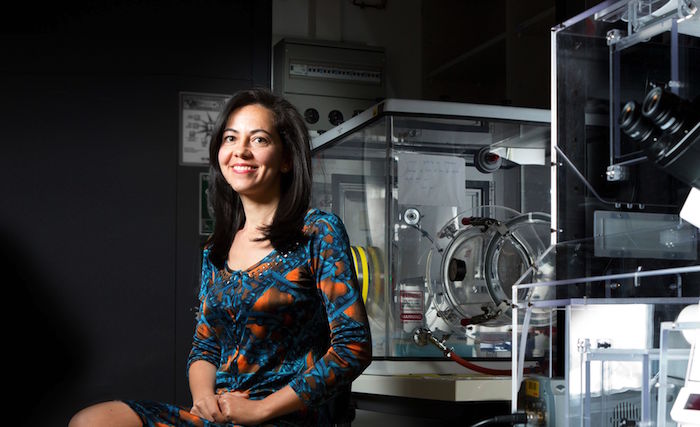

Sara Bolognesi: Laureate of the Summer 2021 EPS Emmy Noether Distinction

Kees van der Beek, chair of the EPS Equal Opportunities Committee,

spoke to Sara Bolognesi of CEA-IRFU in Saclay, France, laureate of the

Summer 2021 EPS Emmy Noether Distinction on her work, her interactions

with other communities, research funding, reconciling work and family

life, and mentoring of young physicists.

Kees van der Beek (KvdB):

My very warmest congratulations with the Summer 2021 Emmy Noether

Distinction for your contributions to, and, indeed, leading role in the

CMS and T2K experiments! Can you explain what your current scientific

interests are, why your experiments are important, and what the stakes

are?

Sara Bolognesi (SB): My present scientific

interest is in neutrino oscillations. Neutrinos are very interesting

particles, but very difficult to study! This is because they are hard to

produce, and once you produced them, they are hard to detect, because

of their extremely weak interaction with matter. Therefore, very large

amounts of neutrinos must be produced for any given experiment, and huge

detectors are needed to obtain the necessary sensibility to pronounce

oneself on physical effects related to them. However, building such huge

instruments is well worth it, since neutrino physics is one of the most

promising avenues to push our understanding of fundamental physics

beyond our present interpretation, the Standard Model. The T2K (Tokai to

Kamioka) experiment seeks to quantify neutrino oscillations (evolution

of one neutrino type into another) through measurement of the so-called

mixing parameters. This can, given sufficient sensitivity, unveil the

symmetries in the neutrino mass ordering and flavour mixing, and most

importantly, a possible violation of charge-parity (CP). This would be a

crucial discovery, while CP-violation has been measured in quark

sector, this would be a new fundamental source of CP-violation and the

first in the lepton sector. We have, so far, made significant steps

towards a measurement of possible violation of CP symmetry in neutrino

physics, but experiments have to be made more sensitive – which is my

aim and that of my team. Remarkably, since the collisions of neutrinos

with the detector material involve their complex, many-body interaction

with the multiplicity of particles composing the target nuclei, reaching

the required accuracy requires an adequate comprehension of the nuclear

physics involved. This is true for both the accurate characterisation

of the emitted neutrino flux, as for the understanding of the scattering

cross-sections in the remote detector. What I love about my work is the

fact that it therefore involves many different communities – every day,

I learn something new!

KvdB: Is the search for

new physics the reason why you made a spectacular move from Higgs physics

in the framework of the CMS collaboration to neutrino physics, and

this, right after the discovery of the Higgs, when results were ready

for the reaping? How did you decide this shift?

SB:

Indeed, after the discovery of the Higgs, the entire team was extremely

excited. However, in spite of the Higgs having been discovered, there

are many questions to which the standard model cannot provide answers.

In particular, it cannot possibly be valid to arbitrary high-energy

scales, so there must be something beyond. An illuminating overview

presented by Hiroshi Murayama from Berkeley at a Higgs workshop in 2013

made it very clear to me that neutrinos are an extremely promising

window to such very high-energy scales. In particular, the standard

model cannot explain why neutrinos have mass, nor why they oscillate the

way they do. Both these phenomena determine the numerical values of a

great many parameters, so understanding them would be a particularly

important step into our further comprehension of nature, and, in

particular, the existence of as-yet hidden symmetries. Practically, I

was greatly helped by the job opportunity formulated by CEA-IRFU, that

did not only propose a permanent position, but did not require previous

experience in the field of neutrino physics – indeed, they were very

open to candidates form other fields. This allowed me to settle and

establish myself both as a scientist and in my personal life. As a

particle physicist, the learning curve in neutrino physics was steep,

but I feel I was truly helped both in my institute and by the welcoming

attitude of the neutrino community.

KvdB:What are the most satisfying – and more difficult parts of your work?

SB:

I love the interaction between many communities and between

experimentalists and theorists that characterizes neutrino physics. The

most difficult part of my position is securing the necessary financial

resources – we are not trained for that as physicists! Here again, I see

the need to go out and obtain funding as an opportunity to learn, even

if this part of the job takes up more and more of our time. We, as

physicists, should accept the manner the world we live in functions. We

must, before publicizing our work in physics and asking for funding,

stop and really ask ourselves whether what we project to do is truly

worth of funding. To have to reflect on this and then explain to

non-experts why society should fund physics is an important and

necessary part of our job. For me, frustration arises when decisions are

made based on political priorities rather than scientific arguments.

While we need a realistic compromise due to the boundary conditions

posed by the world we live in, our primary goal should always be driven

by physics arguments.

More fundamentally, there are better ways in

which a funding process could work. Notably, the very nature of

fundamental physics research requires, at the least, medium-term funding

based on a vision and multi-year strategy submitted by the team, lab,

institute, or collaboration submitting the request, and not the calls

for short-term, individualistic projects that we see all too often

today. At the same time, I’m very worried by the inertia that comes with

increasing size of the collaborations and cost of the experiments. This

not only slows their development but also makes it very difficult to

react and adapt the overall strategy to physics evidence when new

results are obtained.

I, obviously, do not hold the perfect recipe

but our compass should always point to the long-term objective of

advancing physics, no matter how difficult this could be from a

political or funding point of view.

KvdB: You are

obviously very passionate about physics, and that since a very young

age. Where did you get this passion, and how did you choose physics?

SB:

(laughs) You will be surprised to know that at the outset, I first

started on a literary, and not on a scientific path in my secondary

school studies! It was my professor of philosophy in secondary school

who suggested that we read simple texts on modern physics to open our

mind. These were simple texts that addressed issues such as

particle-wave duality, the nature of light, matter, and their

interactions, that had a very large impact on me. I realised that this

touched on something so fundamental for the understanding of our world

that I could not accept to ignore it: I wanted to learn more about it!

My subsequent enrolment in the physics programme at the university of

Torino has lead to two life-changing experiences. The first was my

participation in the CMS-Torino group as of my third year of studies, a

group with several women in leadership positions. All had a rich social

and family life, as well as being highly successful physicists, which

allowed me to project myself in my own possible future. The second was

my work at CERN, in a truly multicultural environment. This was, to me,

as much as a scientific experience, a truly human experience that made

me decide that this is what I wanted for the rest of my life. In the

neutrino community, which involves close collaboration between

physicists from Europe, Japan, and the Americas, I find this

multicultural, tolerant, and very human ambiance once again.

KvdB: Did you ever have problems reconciling your work and your family?

SB:

There have been some difficult moments, but, honestly, I am working in

an environment and for an employer that is extremely respectful of the

balance between work and one’s private life, to the point where the

balance we can achieve here is envied by our foreign collaborators. For

instance, when my partner and I adopted our children, my professional

environment was extremely respectful of our choice and very helpful when

I returned to the laboratory. I cannot help but think that this is

related to the fact that the head of my laboratory, the head of the IRFU

Institute, and the head of our CEA Direction are all women. A difficult

moment was the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic and the first lockdown -

even if I realise that the situation was much harder for so many

others. Where I had, over two years, established a good work-family life

balance, this was now, all of a sudden, overturned. Here I was working

from home, with three children by my side, and required to school them!

The real problem here is not, in my opinion, one of gender, but that of

attaining equilibrium between family life and professional life in

general, whatever the family’s composition. I am very fortunate in that

my husband fully participates in family tasks, including during the

COVID-19 period; having a family that supports me in my professional

challenges is very important for me.

KvdB: You have had many role models in Torino. Do you consider yourself to be a role model now?

SB:

I hope I am! All the more so since, in my group today, there are nearly

as many women as men. We do discuss gender issues as well as family

issues, especially with younger women. I tell them that their life

choice is, of course, theirs. However, they should never make this

choice based on fear. Being afraid that one cannot be a woman and a

physicist at the same time, of “not being able to”, must never be a

criterion for choosing work over one’s private life or vice versa.

Taking responsibility for one’s choice however comes with effort, the

effort to make it work, and the effort to find one’s correct personal

balance. The message I wish to convey is: if you want a career in

physics, go for it, if you love physics, you will manage!

Kees van der Beek (KvdB):

You are in a position of ever increasing responsibilities. Do you have

ideas on how an academic, scientific environment can help empower women

active in its midst?

Sara Bolognesi (SB): That’s a

tough question! There are no easy solutions to this. Nevertheless, I

think two things can help. The first, and most effective in my opinion,

is tutoring, through examples. When one meets a young woman in doubt

about her career choice, having a role model with whom she can interact

or a tutor that serves as an example and build her self-confidence can

really help. At T2K we also have a Diversity group that reaches out to

young women in this sense. The second, and more general point is that we

all, women and men, should make an effort to make our professional

environment less aggressive. Even though academic discussion can be

passionate, we should always be careful to respect the other, and not

try to, for example, undermine the other’s self-confidence. Speak out,

discuss, argue, with passion and conviction, but do so as if you were

speaking to a close family member, your daughter or son, with respect

and understanding. Science is an environment for discussion, where no

one holds the absolute truth.

Sara Bolognesi acting on the valves of the gas system of the near detector (ND280) of T2K - image credit: Sara Bolognesi

Tags:

CEA-IRFU

CERN

EPS Emmy Noether Distinction

EPS EOC

EPS Equal Opportunities Committee

Higgs boson

LHC

particle physics

T2K

women in physics

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Administration,

Monday 30 August 2021

Updated: Tuesday 31 August 2021

|

The Summer 2021 Emmy Noether Distinction of the European Physical Society is awarded to

of

the Institut de Recherche sur les lois Fondamentales de l’Univers –

Institute of Research on the Fundamental laws of the Universe of the CEA

(IRFU) – Commissariat aux Energies Atomiques et Alternatives (CEA),

Saclay, France, “For her development of the data analysis techniques

that conclusively improved the sensitivity of the CERN-CMS experiment,

thus allowing the discovery of the Higgs boson and the first measurement

of its spin and parity.”

Sara Bolognesi is a particle

physicist known for directing several foremost programmes for physical

research, and for making decisive proposals for experiments and

instrumentation. Thus, Sara has been a key contributor to many different

topics in CERN-CMS, including Higgs phenomenology, where she helped in

developing and testing a new Monte Carlo generator (Phantom) to study

Higgs production in Vector Boson Fusion and Vector Boson Scattering; the

first LHC data, where she contributed to Electro-Weak physics analysis

(Z,W+jets production), worked on jet reconstruction, Beta-physics and

quarkonia; and the mapping of the 4 T magnetic field as well as the

detector commissioning for the Drift Tube Barrel muon system. Most

importantly though, Sara developed a Matrix Element analytical

Likelihood Analysis (MELA) to best separate signal from background by

optimizing the use of the information on production and decay angles of

the Higgs. This method increased the performance of the analysis to the

point where the Higgs-like resonance at 125 GeV could be observed at 3

sigma significance in the HZZ4ℓ channel in the summer of 2012. After

that, the MELA method allowed the CMS collaboration to reach the 5 sigma

significance necessary to claim a discovery, making the analysis of the

HZZ4ℓ decay channel in CMS the most significant Higgs analysis at LHC0.

Sara Bolognesi's made a deeply insightful career move when,

after the discovery of the Higgs boson, she changed from her activities

at CMS to the Tokai to Kamioka (T2K) collaboration. Within the

scope of the T2K collaboration, Sara has been instrumental in organising

the community and coordinating the experiments that lead to the first

detection of possible CP violation in leptons. Sara is also very much

involved in teaching, and has had an impressive series of students; she

is often invited to teach in schools. She currently holds a large number

of responsibilities in IRFU as well as in many international committees

and collaborations, where, beyond her decisive scientific input, she is

also a foremost advocate for the cause of women in physics.

An interview from Sara Bolognesi by Kees van der Beek, chair of the EPS Equal Opportunities, will soon be released.

Sara Bolognesi acting on the valves of the gas system of the near detector (ND280) of T2K - image credit: Sara Bolognesi

More info about the EPS Emmy Noether Distinction

Tags:

CEA-IRFU

CERN

distinction

Emmy Noether

EPS Emmy Noether Distinction

EPS EOC

EPS Equal Opportunities Committee

Higgs boson

LHC

particle physics

T2K

women in physics

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Administration,

Tuesday 25 May 2021

Updated: Tuesday 25 May 2021

|

In 2013, the European Physical Society launched the Emmy Noether

Distinction to recognise noteworthy women physicists having a strong

connection to Europe through their nationality or work.

Emmy

Noether, with her fundamental and revolutionary work in the areas of

abstract algebra and on the conservation laws in theoretical physics, is

an exceptional historical figure for all generations - past, present

and future - of physicists.

The laureates of the Emmy Noether

Distinction are chosen for their capacity to inspire the next generation

of scientists, and especially encourage women to pursue a career in

physics. Attribution criteria therefore focus on the candidate’s

• research achievements

• endeavours in favour of gender equality and the empowerment of women in physics

• coordination of projects and management activity

• committee memberships

• teaching activities

Nominators are encouraged to address these five points in their proposal.

The EPS Emmy Noether Distinction for Women in Physics is awarded twice a year, in winter and in summer.

The

selection committee, appointed by the EPS Equal Opportunities

Committee, will consider nominations of women physicists working in

Europe for the 2021 Summer Edition of the Emmy Noether Distinction from

the end of May 2021. As is customary for the Summer Edition of the

Distinction, particular attention will be paid to early and mid-career

candidates.

For the present edition, the nomination deadline is extened to June, 11th 2021.

To make a nomination, please, email the following information to the EPS Secretariat:

- A

cover letter, detailing (in no more than 3 paragraphs) the motivation

for awarding the EPS Emmy Noether Distinction to the nominee;

- The nominee’s name, institution and email

- The nominee’s CV

- The nominator’s name, institution, and email

- Optional: No more than 3 support letters

Download the distinction charter Download the distinction charter

Read more about the EPS Emmy Noether Distinction on the EPS website Read more about the EPS Emmy Noether Distinction on the EPS website

Tags:

call

distinction

Emmy Noether

EPS Emmy Noether Distinction

EPS EOC

EPS Equal Opportunities Committee

women in physics

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Administration,

Monday 17 May 2021

|

Author: Kees van der Beek

Maria Garcia Parajo – Laureate of the Winter 2020 EPS Emmy Noether Distinction / photo: Maria Garcia Parajo

Maria

Garcia Parajo is the laureate of the Winter 2020 EPS Emmy Noether

Distinction. On behalf of e-EPS, Kees van der Beek, chair of the EPS Equal Opportunities Committee, spoke with her on the

application of physics to cell biology, inspirational figures in

physics, and empowerment of women physicists. COVID-19 restrictions

oblige, the interview was carried out remotely.

Kees van der Beek (KvdB):

Maria, again, my warmest congratulations on the occasion of the Winter

2020 EPS Emmy Noether Distinction. Can you shortly describe what you are

currently working on, and why you feel that it is important?

Maria Garcia Parajo

(MGP): For the last ten years, my team and I have been working on how

the internal organisation, in space and in time, of biomolecules inside

living cells regulate cellular functions. We develop optical techniques

and instrumentation that have the necessary ultrahigh spatio-temporal

resolution and sensitivity to detect individual molecules and the events

relevant for cellular functions. Our research thus truly has two sides:

the development of sophisticated optical and biophysical tools, and

then, there is their application in the physiological context of living

cells.

In the first, we have the development of different

far-field and near-field techniques for super-resolved imaging of

individual molecules (on scales much smaller than those imposed by the

diffraction limit of light). Far-field methods typically use stimulated

emission, which was the object of the Nobel prize in 2014, as well as

single molecule localisation methods in which the center of mass of a

given molecule is pinpointed. A near-field imaging technique that we

use a lot in our group exploits plasmonic modes in nano-antenna.

The

second side concerns applications. I wish to cite two examples, in

which high spatio-temporal resolution is particularly important. The

first is related to the pandemic. We all know that the COVID-19 virus

has specific receptors on its outer shell; both the virus and the host

cell membranes can be seen as ligands to these receptors. The manner in

which the receptors organise themselves in space and time determines how

strong the virus attaches to host cells. The spatio-temporal

organisation of the receptors is therefore important to regulate the

affinity of the virus to the host cells. Another example is the

organisation of DNA or of chromatin inside the nucleus. This determines

the basic mechanisms of the cell functions. We are particularly

interested to the immune system and pathogen binding. Finally, there is

the issue of cancer, which is intimately related to the migration and

adhesion of rogue cells in sites where they do not belong. It is the

deep and constant interplay of physics, physical binding mechanisms, and

biology that fascinates me.

KvdB: Can you tell us how you arrived in this exciting field?

MGP:

I followed a long trajectory, starting from electronic engineering. I

quickly realised that the courses that fascinated me most were those

that had to do with physics, including electromagnetism and solid-state

physics. I therefore enrolled in a Physic Masters programme at my Alma

Mater. All the while, I was looking for opportunities to study

solid-state physics, and chose a Master programme in semiconductor

physics at Imperial College. For my PhD, I fabricated semiconducting

quantum dots in III-V semiconductor heterostructures. One of the

bottlenecks was that our fabrication process rendered these structures

highly inhomogeneous. It was therefore very difficult to study their

optical properties, e.g. through photoluminescence (PL), since these

were averaged out by material heterogeneity. This is why I searched for

new approaches to study the PL of individual structures, and had the

opportunity to pursue such during my post-doctoral appointments in Paris

and in Twente in the Netherlands. The challenge in the latter group was

to measure the fluorescence of individual (bio-) molecules at room

temperature. A major breakthrough occurred through my interactions with

Carl Figdor, an immunology professor at Nijmegen university. Together,

we realised that my ultra-sensitive optical technique could be applied

in living cells. For the first time, I could see the signal coming from

bio-molecules, in vivo! This was something really new – a signal from a

living, moving entity! From that initial thrill, I became truly

fascinated with the field that I have never left since.

KvdB: Have you ever considered any of your colleagues as role models? Do you consider yourself to be a role model?

MGP:

I do not really know whether the people who have influenced me in my

career choices, starting with my father, are actually role models or

rather, inspirational figures. Unfortunately, having evolved in a very

masculine academic environment, I find no female figures among them.

When I did my Ph.D. in London, there were only two women Ph.D candidates

in the whole ten-story building! As for me giving inspiration to young

scientists, this is a great and continuous source of pride for me. It is

so extremely satisfactory to see students grow into scientific

maturity, and to be able to create the environment and the conditions

that have enabled them to do so, to modulate their inner capacities to

this end! There are many facets to this route to scientific maturity,

and I endeavour to accompany my students in every way, not only the

scientific aspects. It is important to also address things such as

emotions, fears, uncertainty, insecurity and self-confidence, to be in

dialogue with ones students. My relation with the members of my group is

thus very open. I am particularly proud of being a role model to young

female scientists.

KvdB: Did you know that you were nominated for the Emmy Noether distinction?

MGP: A

couple of my colleagues had actually suggested that I would be a good

candidate. However, from there, I was conscientiously kept out of the

loop, and to be laureate was a very happy surprise.

KvdB: You have been recognized through many prizes and awards. Is the Emmy Noether Distinction still special for you?

MGP: Yes

it is, because it does not only recognise one’s scientific career, but

also all the extra effort that one has put into promoting and empowering

women to excel in science. Through it, the European Physical Society

recognises the specific importance of empowering women and promoting

gender equity and that is very important to me.

KvdB: Have you yourself encountered any difficulties rooted in gender roles or inequity?

MGP:

Definitely, women are much more aware of their position than we were in

the day. They are much more aware of the things that they need not

accept or take for granted. When I was a student, I took the fact that I

evolved in a mainly male environment as a sort of “default” situation. I

started to feel the resistance against my career progression at the

point where I became a post-doc and then wanted to establish myself as a

young professor, and I found myself competing for grants, for papers,

for last authorship, for students. That was a tough part of my career –

unfortunately, many young women researchers still find a particular

resistance at that stage of their career today.

KvdB:

What actions do you think are most useful to help women in physics?

Which one of your actions do you see as having been the most successful?

MGP:

The problem of the position and career progression of women in physics

is a very complicated one because it has a great man inputs. You

therefore have to target many factors in parallel, something that will

probably take generations. Yet, one of the most important things is that

everyone, women and men, in the field is aware, is conscious of the

implicit gender bias that still pervades our communities today and

affects the working environment. It is the accumulation of many little

things on a daily basis that causes women to snap and leave science. I

really do believe that explicit bias is no longer the problem today. I

also think that specific training courses in secondary and soft skills

for women scientist are very important. Science is a highly competitive

business and women have to acquire the necessary assertiveness, and the

assurance to speak in public and put themselves on the front of the

stage. Mentoring is also a very important point. Like I do with my

students, it is necessary for more senior scientists to advise young women

physicists how to handle uncertain, difficult or uncomfortable

situations. On the other hand, I do not believe in positive

discrimination or quota. To me, all discrimination is negative. Rather,

as a way to avoid discrimination, I would like to recommend the creation

of specific calls for women scientists (physicists), in the same way as

calls can be targeted towards age groups, e.g. early career

researchers. In any case, one will always have to make that extra

effort, that extra little thought, to ensure that women get equal

chances at all levels, be it employment, conferences, or other.

KvdB:

COVID-19 has aggravated all that is not well in the world. What are the

difficulties related to the COVID pandemic that you or your students

encounter?

MGP: Of course. The pandemic is a

major distraction from all points of view. We have had to stop all

experiments. When we resumed, it was not the entire group that could

return. Worse, in our case we are dealing with biological reagents, to

obtain them afresh comes with major delays. 2020, however, has proved

productive as far as data analysis and paper writing is concerned. I am

afraid that the reduction of scientific productivity will be felt in

2021. More generally, we are all human so the pandemic affects us all. I

have spent much more time giving emotional support to members of our

group. Our group is very international, and many of its members went

back to their home country, without always having the possibility to

come back. To remain close to, and help our younger colleagues of the

next generation is an extremely important part of our responsibility.

Read about the EPS Emmy Noether Distinction Read about the EPS Emmy Noether Distinction

Tags:

cancer research

cell biology

EPS EOC

EPS Equal Opportunities Committee

instrumentation

interview

women in physics

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Administration,

Monday 15 February 2021

Updated: Monday 22 February 2021

|

The Winter 2020 EPS Emmy Noether Distinction is awarded to:

ICREA Research Professor and researcher at the Institut de Ciències Fotòniques (ICFO) in Castelldefels near Barcelona in Spain « for her outstanding contributions to nano-biophysics and to numerous programs to support women in physics ».

At

ICFO, María García Parajo is the leader of the Single Molecule

Biophotonics group of IBEC-Institut de Bioenginyeria de Catalunya. She

received her Ph.D from Imperial College, University of London, UK, in

1993, from where she proceeded to take an Assistant professorship at the

University of Twente, the Netherlands, where she worked for four years

in the Applied Optics Group at MESA+ / Institute for Nanotechnology. She

moved to Barcelona in 2005 and has worked there ever since.

María

García Parajo has contributed decisively to several technical

developments that allow the mapping and the direct visualisation of

biomolecular interactions regulating life´s essential processes. The

methods she has pioneered and used have provided profound insights on

the spatiotemporal organisation of the plasma membrane of cells, which

influence diverse processes in the immune system such as pathogenic

infections (including HIV pathogenesis), autoimmunity and immune cell

migration (with direct implications in proper immune regulation and

cancer). One of her salient results (published in Cell in 2015) has led

to the direct visualisation of chromatin inside intact cells, which

allowed for the first time ever to correlate chromatin compaction to

cell differentiation.

María García Parajo has contributed

tirelessly to physics education via summer schools and training

programmes as well as by the furthering of equal opportunities and

gender equality in physics. María has contributed to and participated in

a great many activities, committees, talks, seminars, round-tables

panels, etc., oriented at creating opportunities for women scientists.

Since September 2017, María García Parajo is part of the Gender

committee at ICFO, where she has initiated a large number of actions to

increase the visibility, awareness & empowerment of young talented

female researchers promoting the successful construction of their

academic career.

Prof. María García Parajo - image credit: ICFO

Tags:

EPS Emmy Noether Distinction

EPS EOC

EPS Equal Opportunities Committee

gender equality

ICFO

nano-biophysics

nanotechnology

women in science

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Administration,

Monday 7 December 2020

|

Author: Claudine Hermann, EPWS President, Femmes & Sciences Vice-President

The 20th anniversary of the French association of Women in Science took place on 20-21 November 2020

A

team of highly motivated members began to prepare this anniversary one

year ago. The programme was very ambitious: two sessions related to

enterprises and schooling over a day plus a full day session for the

members, an exhibition of art photos of women scientists on the railings

of Paris Town Hall. But then a first 2020 COVID-19 lockdown occurred in

spring, then a second one this autumn… Multiple readjustments were

necessary, following the new pandemic rules. Finally one session and the

exhibition have been postponed to 2021, and two sessions were adapted

to videoconferencing (by very expert volunteer members!).

On the afternoon of November 20th

the session “Girls Studies Orientation towards Science – Status Quo and

Leverages” primarily targeted teachers (and was an official training

for over 100 of them) and the general public. There were 351 attendees,

from the different regions of France and also from Ivory Coast,

Madagascar, West Indies, Hong Kong, Singapore… After a talk by an

Education scientist on studies and survey results about the choice of

science by girls, the next speaker trained the teachers on “Fighting,

Identifying and De-Crystallising Stereotypes”. Then the different tools

for teenagers and educators on science orientation for young people,

realised by the association Femmes & Sciences (F&S), were

described. Finally a “speed-meeting” allowed five women scientists of

various ages and disciplines to introduce their career path and their

scientific activity. The audience appreciated very much that afternoon

and in particular the testimonies: even if F&S members are visiting

many classes in various parts of France, unfortunately they cannot go

everywhere!

The last session on November 21th during Saturday

morning, “We, the F&S members”, was for members only; 86 of them

were connected out of 350. After an introduction by Nadine Halberstadt,

F&S President, who pointed that it was the first time that the

association was organising such a session for members only, the

attendance was split into groups of 10 persons in “ice-breaking”

parallel sessions. Then each French regional group presented their

activities (tools for teenagers, exhibitions, career descriptions for

teenagers or teenager girls, mentoring of PhD female students, documents

for teachers against stereotypes or presenting portraits of women

scientists of the past and of nowadays…). Next came the analysis of the

results of a survey launched by F&S, and having received almost

3.000 answers, on the way women and men scientists experienced the

COVID-19 period. In the final discussion the participants expressed

their interest in renewing such a session, which allows members to know

better each other and regional groups to take advantage of the other

groups’ experience.

Tags:

EPS EOC

Femmes&Sciences

gender equality

outreach

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Administration,

Monday 12 October 2020

Updated: Thursday 15 October 2020

|

Author: Luc Bergé

Hatice Altug is professor in the Institute of Bioengineering at Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Switzerland since 2013. She is also director of EPFL Doctoral School in Photonics. Between 2007 and 2013, she was professor in the Electrical and Computer Engineering Department at Boston University, U.S. She received her Ph.D. degree in Applied Physics from Stanford University (U.S.) in 2007 and her B.S. degree in Physics from Bilkent University (Turkey) in 2000.

At EPFL, she is heading the Bionanophotonic Systems Laboratory with around 15 talented graduate students and postdocs from around the world. Her research is focused in the field of nanophotonics and its application to biosensing, spectroscopy and bioimaging with the aim to introduce nanodevices with significant importance for fundamental life sciences, early disease diagnostics, and point-of‐care testing. Her laboratory is specialized to exploit novel optical phenomena at nanoscale and metamaterials by using nanophotonics, nanofabrication and microfluidics.

Prof. Altug is the recipient of the EPS Emmy Noether Distinction, Adolph Lomb Medal from The Optical Society (OSA), and the U.S. Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers. She received a Consolidator Grant from the European Research Council (ERC), an ERC Proof of Concept Grant, the U.S. Office of Naval Research Young Investigator Award, U.S. National Science Foundation CAREER Award, Massachusetts Life Science Center New Investigator Award and the IEEE Photonics Society Young Investigator Award. She is the winner of the Inventors’ Challenge competition of Silicon Valley in 2005. She has been named to Popular Science Magazine’s "Brilliant 10" list in 2011.

Luc Bergé, President-Elect of the EPS and chair of the EPS Equal Opportunities Committee (LB), interviewed Hatice Altug (HA).

LB: Why did you choose to study physics?

HA: Since my early years in middle school I got fascinated with science subjects and encouraged by my physics teachers. I was getting curious about the scientific origin of the things that I was observing in nature, technological inventions and how machines work. In order to satisfy my curiosity and get a better understanding of science I decided to major in physics. I also knew that physics is a fundamental subject and if I studied physics I would be well equipped to get into different scientific fields more easily.

LB: Any worry to match your family life and a career in physics?

HA: Yes, it is not always easy to balance a family life and a career in physics. For example, travelling is important for a scientific career in order to attend or organize conferences, participate in consortium projects, committees or visit other universities. But, travelling also requires time and sometimes I find it challenging to accommodate it with family duties.

LB: Were you worried about finding a job in physics?

HA: There are different job options for a physicist including in academia, industry and education. I was aware that finding an academic job was more challenging than in industry due to the limited available positions. Academy is a competitive environment, irrespective of the gender, and, I knew that to get a good position it was necessary to produce high quality work which required consistent dedication and perseverance during my graduated studies. Rather than being worried I focused on my research to achieve my goals. Examples of successful graduates around me who made their ways to a faculty position gave me further confidence that I could also make it.

LB: What has been the personally most rewarding experience so far in your career and also the biggest difficulty encountered so far in your career?

HA: From my PhD times I still remember the excitement and joy I had when my experiments finally worked after many trials and failures. I also remember the happy feeling after my first scientific paper got accepted in a peer-reviewed journal. I live through the same joy and happiness with each of my PhD students every time they experience such milestones. One of the most rewarding aspects of my career is to be part of their academic journey and guide them to succeed. Currently, the main difficulty is managing the time. As you progress in career you tend to get more responsibilities, expectations, and obligations to fulfill and it gets harder to manage all of these at your best with limited time.

LB: Did you encounter any difficulty in finding funding for PhD or a post-doc position related to the fact that you are a woman?

HA: I did not feel that I was discriminated negatively in finding funding because of my gender.

LB: Any suggestion to guarantee a balanced gender representation in physics?

HA: Due to the leaky pipeline few women choose to climb in the career ladder in physics, and science in general. Young girls are interested in math and science at the start but they choose to drop it later. As one of the factors, associating the stereotypical scientist images with men cannot resonate well with young women. In this regard having more successful women physicists could serve as role models and inspire them to continue in physics. Family balance is also an important factor in the leaky pipeline and institutions should give more family support (child care, career breaks etc) to young women so that they do not give up their career.

LB: Any particular advice for a young aspiring researcher?

HA: Choose a research topic that you are most passionate about and work on a problem that you believe you can make a difference. This will give you the power, self-motivation and confidence to succeed. Also, keep your spirit of newcomer always alive as it helps to improve yourself continuously by learning new things.

LB: Do you have any female ‘physicist cult figure’ or ‘role model’?

HA: While I was in high school Marie Skłodowska Curie has been the female physicist cult figure for me. Once I started university, I got to learn other female scientists like Emmy Noether, Maria Goeppert Mayer, Ada Lovelace, Chien-Shiung Wu. At the same time, it is easier to take someone as a role model from your closer surrounding and get connected with. In my undergrad years I was the only woman in my class and there were no female professors in the physics department to look up to as an example. Still, I was fortunate to be supported by my advisors and professors irrespective of their gender and used my energy to focus on science. On a positive side, during my PhD years and also later in my career I encountered amazingly successful female scientists who continue to inspire me.

Prof. Dr. Hatice Altug

Tags:

biology

distinction

EPFL

EPS EOC

EPS Equal Opportunities Committee

gender

light-matter interaction

nanophotonics

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Administration,

Monday 14 September 2020

Updated: Tuesday 15 September 2020

|

Author : Gina Gunaratnam

The European Physical Society aims at promoting physics, especially among a young audience. In 2020, the Society published a calendar called "Inspiring Physicists".

The idea of this calendar obviously came to me as a way to put forward the laureates of the EPS Emmy Noether Distinction and to provide examples of living and committed scientists. It shows the variety of research fields in physics and wishes to inspire the young generations in their choice of studies. The calendar also presents some famous female figures.

Furthermore, the EPS regularly publishes interviews of inspiring young female physicists. Lucia Di Ciaccio, former chair of the EPS Equal Opportunities Committee, launched the idea in 2015. These interviews can be read online.

Every month of this year, a new physicist can be discovered in the calendar. The first version puts forward ladies only, because they are often under-represented in various areas of physics (scientific school books, history books, conference speakers, scientific reference).

Our calendar was distributed to our members in Europe and worldwide. Due to the SARS-CoV-2 crisis, the development of the actions started in schools or conferences was suddenly reduced and the follow-up made less easy. However, very positive feedback already came from our members before lockdowns : distribution to physics teachers at conferences, use as educational medium to raise interest in sciences in classrooms or training schools and in an exhibition of famous women.

We hope that with the help of enthusiastic teachers and scientists, our calendar will inspire young pupils to study physics and to give them the taste of science in 2020 and beyond.

Left: the calendar cover with the names of the physicists presented inside - Right: the EPS Distinction for Women Physics is named after the mathematician Emmy Noether

More info :

Tags:

EPS EOC

EPS Equal Opportunities Committee

women in science

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Administration,

Monday 14 September 2020

Updated: Monday 14 September 2020

|

Author: Luc Bergé

Maria Viñas’s research focuses on the physics of vision and vision

psychophysics, with Adaptive Optics based visual technologies to image

the eye, and study visual function and neural adaptation in

polychromatic conditions under a very wide range of

artificially-simulated-conditions. Her work on Adaptive Optics visual

simulation in polychromatic conditions has contributed to different

areas of research in Visual Optics and Biophotonics, like the study of

chromatic aberrations in phakic and pseudophakic eyes and their impact

on vision, the optical, visual and neural effects of astigmatism, the

experimental simulation of complex multifocal solutions for Presbyopia,

and the pre-operative simulation of post-operative multifocal vision

with those corrections. Maria Viñas completed undergraduate studies in

Optics and Optical Engineering in the Complutense University of Madrid

(UCM), followed by a predoctoral work at the Visual Optics &

Biophotonics Lab, where she obtained her PhD in Physics in 2015. She is

currently an IF-MSCA fellow with a joint position at the Wellman Center

for Photomedicine, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical

School (USA) and the Institute of Optics of the Spanish National

Research Council (Spain). She is also founding member of the spin-off

company, 2EyesVision, which develops clinical visual simulators.

Maria

Viñas received several recognitions from scientific societies (OSA,

ARVO). In particular, she was elected OSA Ambassador of The Optical

Society (OSA) in 2019. She is past president of IOSA - Institute of

Optics OSA Student Chapter - where among a wide range of activities she

has authored a very successful book of optical experiments. She is

currently the vice-chair of the Visual Sciences Committee of the Spanish

Optical Society, and chair of the Women in Optics and Photonics

committee of the Spanish Optical Society, where she fights gender

stereotypes in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

Luc Bergé, President-Elect of the EPS and chair of the EPS Equal Opportunity Committee (LB), interviewed Maria Viñas (MV).

LB: Why did you choose to study physics?

MV:

I actually studied Optics and Optical engineering at the University

Complutense of Madrid. However, I became more and more interested in the

Optics/Physics behind the visual process and related technologies. That

is why, when I finished my Master’s degree, I joined the Visual Optics

and Biophotonics Lab of the Institute of Optics of the Spanish National

Research Council (CSIC). The group, led by Prof. Susana Marcos, had a

research line focused on the use of Adaptive Optics technologies,

inherited from astronomy and only very recently focused on visual

Optics, in order to study the optics of the eye and how the brain sees

the world through it. I was fascinated by that topic. The same

technology used to image the stars could be used to image the eye! Also,

I did my PhD there, developing novel Adaptive Optics systems to study

visual function and to improve optical corrections for visual problems,

like Myopia or Presbyopia. And I am really happy to see that some of

those technologies have jumped from the lab to the clinic, via a

spin-off company, 2EyesVision, which I co-founded. Now, I am really

excited to keep pursuing novel breakthroughs in the new phase of my

career, starting now as an IF-MSCA fellow with a joint position at the

Wellman Center for Photomedicine, Massachusetts General Hospital and

Harvard Medical School (USA) and the Institute of Optics of the Spanish

National Research Council (Spain).

LB: Any worry to match your family life and a career in physics?

MV:

Funny timing for that question, since I am now a postdoctoral

researcher with a 5 months old baby, and that fact has a real impact on

my work/life balance. I was not worried about this before; I did not

even think much about it. I could see my female colleagues struggle, but

I did not relate much. Now I am facing the real truth, I can say that

this situation is hard, but doable.

We all know that research

provides a very competitive environment, which requires carrying a high

workload and a lot of travelling, among other things. Numbers of female

scientists in STEM tell us that the struggle is higher for women. This

happens even before we consider having a family; it is deeply related to

gender stereotypes that affect us all. Also, the number of female

scientists in STEM areas is lower, because of the work/life balance,

which is typically harder to maintain for women. However, I am

optimistic about the future. Things are changing. Research/Academic

institutions are making an effort to attract female talents to STEM and

to maintain it by offering more flexibility, looking for strategies that

enable more diverse research teams or fighting stereotypes. There is

still much to be done, but I really think if you want to pursue a career

in STEM, this issue must not discourage you. It is so much fun to work

in the lab (as Prof. Donna Strickland said in her Nobel Prize

presentation) than the rest can be overcome.

LB: Are you worried about finding a job in physics?

MV:

I think when you are at a postdoctoral stage you certainly worry about

this. There are many options to explore, and you can join truly amazing

groups and develop very interesting projects. However, getting a

permanent position, in such a way that you can develop your own

independent projects and lead your research group is not so easy. I

think this is a common worry for many researches at this time: you love

your work, which is quite exciting, but your career is not as stable as

you’d like. In my case I have been very lucky so far, I cannot complain.

LB: What has been the personally most rewarding experience and also the biggest difficulty encountered so far in your career?

MV:

For me the biggest difficulty was the beginning. After graduating, I

started working in Industry, nothing related to research. However, I

desired something else. I knew I had found my path when I started my

PhD. I really like what I do. My most rewarding experiences have to do

with teaching, not only my students in the lab, but also students in the

University or children in outreach activities. How their curiosity

awakes, how they grow scientifically, is very rewarding.

LB:

Did you encounter any difficulty in finding funding for PhD or a

post-doc position related to the fact that you are a woman?

MV:

I was unaware of gender bias during my pre-doctoral years; I was happy

because I could focus on Science, only lab stuff mattered. However,

becoming a postdoctoral researcher changed my perception of things.

Scientific structures are more willing to incorporate male scientists

than female ones. Scientific networking is male dominated, how positions

are achieved, how connections are made…When you are the female

scientist in the room is always more difficult to make your voice heard,

no matter your experience, no matter your seniority, this can undermine

your confidence as a scientist. But I think that things are changing;

research groups are more and more diverse, which helps fighting gender

discrimination.

LB: Any suggestion to guarantee a balanced gender representation in physics?

MV:

For me the important thing here is to fight against gender stereotypes,

which are at the very centre of the problem. This is not only a

question of getting a balanced gender representation in physics, it is

also a problem that affects society as a whole, and which we should be

fighting together. Reducing unconscious bias is the real deal.

LB: Any particular advice for a young aspiring researcher?

MV: Enjoy what you do. A research career is tough, but it is also worthwhile.

LB: Do you have any female ‘physicist cult figure’ or ‘role model’?

MV:

Yes, I have been very lucky in that regard. I had a great professor

during my Master, Prof. Maria Luisa Calvo from the School of Physics of

the Complutense University of Madrid, who was truly inspiring. She went

on being a great mentor along the years. Of course, my PhD supervisor,

Prof. Susana Marcos from the Institute of Optics of the Spanish National

Research Council (CSIC), who taught me almost everything I know on

visual optics and about being a scientist, always supported me to

develop novel breakthrough projects.

Tags:

EPS EOC

EPS Equal Opportunities Committee

gender equality

OSA

RSPS

Visual Optics and Biophotonics

Permalink

|

|

|

|